I have been working with numerous customers lately using Release Flow to support highly reusable Terraform deployments. There are a number of practices that have been in place within the community, some of which I will proclaim are bad (and have done so repeatedly and publicly). The practice described in “Terraform Up and Running” whereby repositories hold subdirectories for each deployment is one I have had in my cross-hairs for years and I am taking aim at it again, here.

Why is it bad to have subdirectories for different environments?

Many like to argue against my assertions that it is bad. I think the is popular for a couple of reasons. First, it was printed in a book, so folks give it some form of reverence. Second, and a big reason for the popularity of Terraform, this is all approachable for people without a development background. However, that isn’t a good reason to perpetuate a bad practice. Just because Terraform is approachable for non-developers doesn’t mean it is okay to rest on that. It means non-developers have some news skills that start to dabble in the developer space and it is an opportunity to learn more about these practices and become better.

Subdirectories are a solution to overcoming some challenges, but the challenges exist because of a foundation of other bad practices. The argument is that “my different environments are not the same, so I need different code.”

The first failing is that Terraform accommodates for differences with the use of variables. Instead of hardcoding differences, implement variables that allow for inputs that vary based on the requirements. If that doesn’t seem obvious, that just means more time should be spent trying to understand why that is the best way to handle it and how it should be accomplished, but that is more than I am going to cover here.

Having subdirectories fundamentally breaks many of the purposes for different environments. Having some code that is applied to lower environments and works its way to higher environments is based on the need to have some form of testing of that code, automated or manual. If the code is copied and pasted to a new directory where it can drift, it is no longer the code that was tested in the lower environment and the value of testing it in the first place has been lost.

Using variables allows for different inputs based on the particular deployment.

Release Flow solves this issue

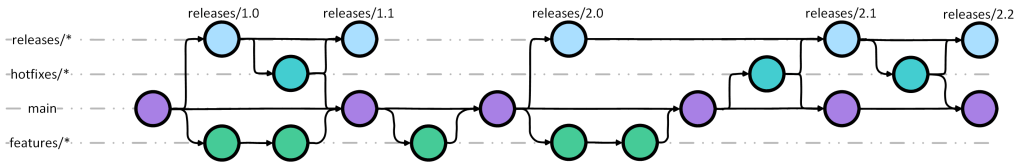

There are numerous ways to accomplish this, including Git Flow. Git Flow has many criticisms, but it does work rather well for Infrastructure as Code. In Git Flow, there are numerous long-lived branches that would be aligned to different deployments. When changes are introduced into the code, feature branches are created; these feature branches would be aligned to a “dev” environment. When they’re ready to be merged, they would be merged into a “develop” branch which would align to a “test” environment. Finally, the changes could be merged to the default branch that would align to the “production” deployment. That doesn’t seem particularly onerous. However, what if there is more than one production deployment? They could all be aligned to the default branch, but then there is less control over the roll out into the various production environments. That may even be the specific purpose of multiple production environments, segmenting the user base and being able to use a canary release strategy so that the entirety of all production isn’t affected at the same time. To accomplish this with Git Flow, numerous long-live branches, one per deployment, would exist. If there are deployments for DR, resilience, stamping out numerous customer environments, this becomes unwieldy.

This is where Release Flow comes into play. In release flow, feature branches are still used, but they are merged into the default branch, which would then be used to test the code and apply it to the “test” environment. However, the default branch would remain as the only long-lived branch. Once that code is ready for production, a new release is created in the form of a medium-lived branch called a release branch. The various release branches would be limited to some supportable number, perhaps N-2. Then, the various deployments would be aligned to the releases and could be changed in any desired pattern. Perhaps there is a “hero region” and it would receive the changes first, then other production deployments would be updated after some time. Whenever a release is no longer being used, that release branch is pruned.

This works extremely well with Terraform Cloud/Enterprise as each deployment would have a dedicated workspace and the workspace could be updated to use different release branches throughout its lifecycle.

However, this can be accomplished with GitHub Actions, as well. It relies on the use of repository environments to stand in for the variables/secrets aspect of a workspace (state still has to be accommodated, but that is easy enough). Each deployment would have its own environment which is just a separate scope to set variables. To align an environment with a particular branch, we can create an environment specific variable called “RELEASE” and set its value to the “ref_name” of the branch.

How we just need a way to have a workflow use this information. An environment is referenced using the jobs.<job_id>.environment property, but that is often hard-coded, which isn’t desirable; it would necessitate a different workflow for each deployment which provides many similar challenges to different directories, but for deviations in the workflows. One workflow to rule them all would be great.

Release Flow with Strategy Matrix

Strategy Matrix is a feature within GitHub Actions workflows to have multiple builds execute in parallel with different inputs. These inputs could dictate the environment. So, this was the approach I started with, but it has many challenges of its own. I started by querying the list of environments using the GitHub client and then querying the value of the RELEASE variable for each environment to build the list of environments to associate with a given execution of the workflow. However, we cannot query the environments’ variables with the permissions available in the workflow token and creating another token should be avoided, if possible; it is just more friction that is unnecessary.

So, the trigger for the workflow is any push to a branch following the ‘releases/**’ pattern. Then, we narrow it down to only executing against environments where github.ref_name == vars.release. That would be great, but the condition provided by jobs.<job_id>.if is evaluated before jobs.<job_id>.strategy.matrix. Since that is used to determine the environment, we cannot use the environment specific variables in the condition, as it creates a “Catch 22.”

So, the next consideration was to create two jobs, the first to get the list of environments, and the second to use that as a matrix and then build a new matrix to filter the environments that shouldn’t be executed against. The issue here is that the outputs from a job that uses a matrix are not all available; it is a race condition created by only the outputs from the final matrix execution being available. So, the second job creates an artifact for each environment that should be included, and then we need a third job to pull them all together by downloading the various artifacts and building a new matrix that is used by the fourth and any subsequent jobs.

The Result

The final workflow example follows:

The fourth job just echos the environment that is being executed. Within the repository, I have four environments, so it split from one job, to four separate threads in the second job, down to one for the third job, and then branches back out to as many threads as there are appropriate environments. In my repository, “releases/1.0” has two environments, and “releases/1.1” has on environment.

The fourth job would include performing a Terraform Plan and another other quality checks. A fifth job could be used to perform a Terraform Apply.

Example repository: https://github.com/dustindortch/github-actions-release-flow